January 28, 2022

Padri’s Immortal Master

On January 30, 1969, Meher Baba called Padri from Meherabad to Meherazad for seven days. As he was leaving Meherabad, Mohammed, the God-intoxicated Mast, said, “Padri will come back tomorrow.” When he was told that Padri was to stay with Baba for a week, Mohammed clarified, “Tomorrow, Dada [Baba] is coming here and is going to join Gustadji [who had died].”[i]

After Padri arrived at Meherazad on his motorcycle, Baba told him that he would have duty the next day and should come when called. That night, Baba began having violent, painful spasms. At 3:30 a.m He called Padri to Him, along with Eruch, Pendu, Bhau, and Goher. The spasms were so bad that they lifted Baba off the bed, and the Mandali had to hold Him down by the arms and legs. Later, at 8:00 a.m., He called Padri back along with more of the men and women Mandali. He told them, “Goher is not responsible for my health. Remember this, that I am God!”[ii] Then the spasms began again.

At noon, seeing that the Western treatments weren’t working, Padri began to use his extensive knowledge of homeopathy to try and help Baba. But at 12:15 p.m., Baba had an excruciating spasm that made Him choke. And then suddenly, unexpectedly, He left His body—left it bereft of His warmth, His humor, His constant, meticulous human presence. According to some accounts, the last gesture He made in this life was to tease Padri about his skills in homeopathy.[iii]

When at last the group had come to grips with the fact that Baba was no longer in the body, Padri got on his motorcycle and headed back to Meherabad as Mohammed had predicted. He opened Baba’s Samadhi, which had been waiting for His physical form since 1927, and prepared it for his Beloved, removing the stone flooring so that Baba’s body could be placed within it.

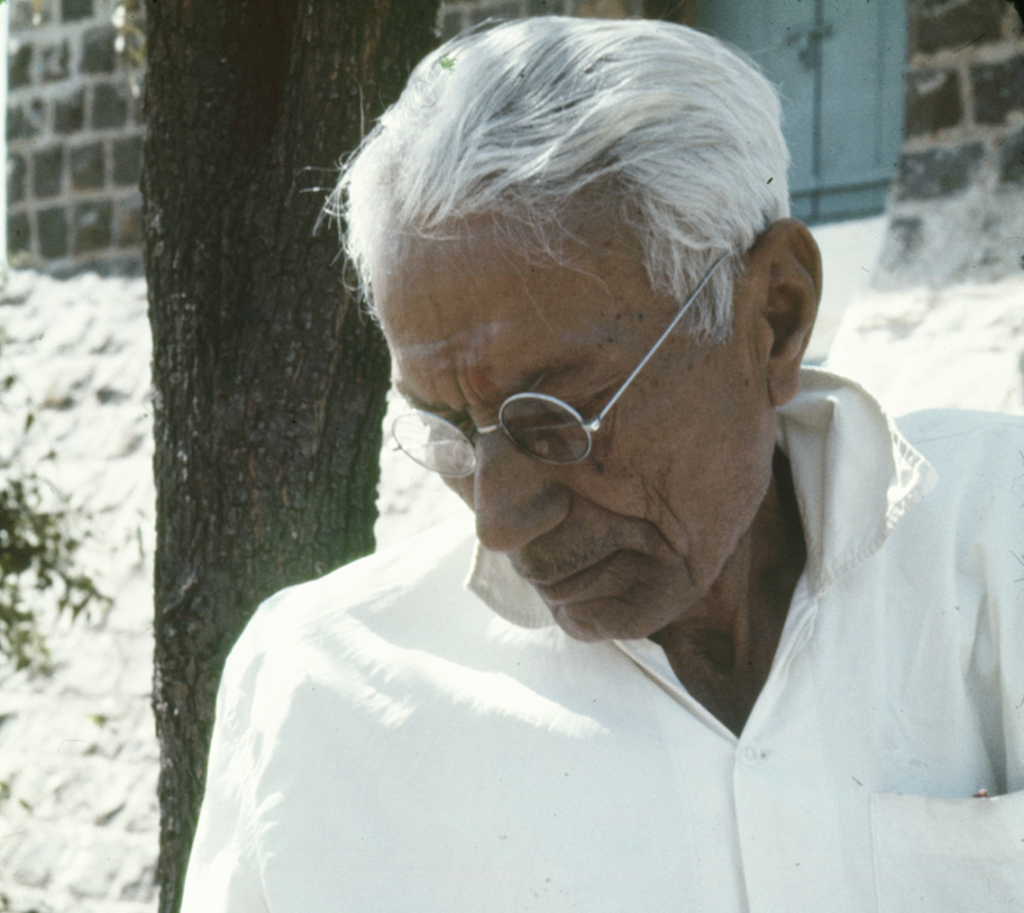

Padri had been with his King since 1922 when (as he once explained to visiting pilgrims asking for a “Baba story”) he promised his mother to visit Baba; was charmed by the atmosphere; and stayed.[iv] He was a talented machinist, a quiet authority, a great problem solver, and always an obedient slave to his Master, whom he often referred to in exalted terms such as “the King” or “the Emperor.” Baba had stationed him for decades as one of the four “pillars of Meherabad,” responsible for the constant upkeep and care of that holy place.

And now, Baba’s order meant dealing with the logistics of the sudden river of Baba’s lovers arriving from all over the world to see their Beloved in the flesh one last time. That first year, when it was all so unexpected, this meant tasks like putting up signs and managing the constant overflow of vehicles and people. But Padri would remain the key executor of Amartithi logistics (which would soon involve lodging and food and tents and generators and water pumps and bathrooms) until his death in 1983.

A Mandali member told a pilgrim once that Padri was the only of Baba’s companions whose life didn’t change after that first Amartithi when He dropped His body. The pilgrim asked Padri if that could possibly be true. He replied, “I’ve got everything and the Giver of everything. Why should I change? You understand? … I got the blessing, I got the giver of the blessing, and He’s still there. And I’ll keep on getting it. So why should I change? Look, isn’t that enough? I don’t want anything more, that’s enough for me.”[v]

In the 1970’s, Westerners started coming to Meherabad as residents, and as Meherabad’s chargeman, Padri ended up managing much of their work and accommodation. Alan Wagner, one of those early residents, talks about working with Padri. “It was just so uniformly there—that support of him being there, of him taking the responsibility, upholding all of us resident volunteers … he supported us always to do the right thing. People talk about how authoritarian he was, very strict—I never experienced that from him, honestly. All I experienced was insight, compassion, support, understanding. But the authority was there and if he needed to use it he could use it.” Alan describes that Padri’s deep respect for others and his willingness to take full responsibility made that authority impeccable. “He was so worthy of admiration, and he so didn’t care.”

Padri rarely talked about his continued inner relationship with Baba after He dropped the body. “I’ve got no sentiments,” he once said to an interviewer who pressed him on it. “I know only obeying the Master.”[vi] But whether he was cycling around in his old Indian Army-issue tennis shoes keeping an eye on every detail of Amartithi; making one of a million practical daily decisions about Meherabad’s upkeep; or teaching a resident about gooseberry jam; Alan describes that those near Padri could sense a “rarified atmosphere,” could feel the Master’s living presence by the remarkable being and relentless work of His slave.

And there were moments, too, when one caught a quiet glimpse of a constant, intimate connection. Heather Nadel, another Meherabad resident, describes one at the end of the wonderful book on Padri, All These Things Take Time, Mister. Sometimes, when no one was around, Padri would sit on the verandah in Lower Meherabad and quietly recite poetry to himself. She remembers one day especially vividly because it was one of the last times she saw Padri before he passed away. “It struck me, the way he was relaxed, it wasn’t as if he was reciting for his own amusement. He was talking to Baba; he talked to Baba all the time. It seemed so private and intimate. And even from way down at the other end of that long verandah, I still got the impression of his being with Baba, of talking to his Master.”[vii]

[i] Lord Meher Online, p. 5399

[ii] Lord Meher Online, p. 5401

[iii] All These Things Take Time, Mister, by Eric Nadel, p. xv

[iv] All These Things Take Time, Mister, by Eric Nadel, p. 21

[v] Padri, Interviewed at Meherabad, India, 1981 & 1982, Video, AMBPPCT 1983

[vi] ibid.

[vii] All These Things Take Time, Mister, by Eric Nadel, p. 156